Step up your async game with PromiseKit

Some of the most engaging apps we use today are apps that require network connectivity of some kind. They communicate with an API somewhere to fetch and store data for example. Or they use an API to search through a huge amount of data. The point is, you don't want your application to sit around and wait while an API call is happening. The same is true for a computing task that's heavy, for example resizing an image or storing it to disk. You want your UI to be snappy and fast. In other words, you don't want to do your heavy lifting on the main (UI) thread of a device.

Taking something off of the main thread

There's several ways to take something away from the main thread. An NSURLConnection automatically performs requests in the background and uses delegates to make callbacks about progress or completion for example. You can also use the dispatch_async function to make something happen on a different thread. While this works perfectly fine it's not very ideal. When an NSURLConnection performs it's delegate callbacks it has to be coupled to that delegate. Also, imagine you want to chain together a couple of network requests; it will start to become kind of messy to keep track of everything.

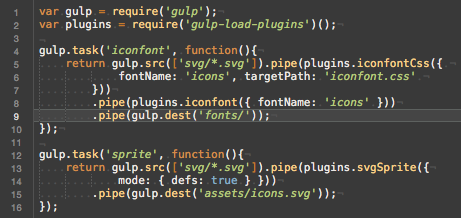

Now imagine an object that you can pass around, it will automatically perform a task once it's done what it's supposed to do. These tasks can be chained so if you want to chain multiple things together it's very simple. Or maybe you want your callback to fire only if a couple of tasks are complete. Imagine implementing that with multiple NSURLConnections. You would probably have multiple instances and whenever one is complete you check the status of the others and then when all are complete you can actually execute the code you've been meaning to execute. That sounds a lot more complicated than just writing:

wait(request1, request2, request3).then { (result1: NSData, result2: NSData, result3: NSData) in }The above snippet is actually really close to how PromiseKit works. Let's explore that a bit further, shall we?

Note: I am going to apply

PromiseKitto network requests for this post. The concepts actually apply to anything that you want to do asynchronously.

A simple Promise example

To demonstrate a simple Promise we'll make a network request. First we create an NSURLRequest that we'll pass to an NSURLConnection. Then we kick off the loading with a Promise so we can use the result once the request is done:

var req = NSURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "http://example.com/api/feed/")!))

NSURLConnection.promise(req).then{ (data: NSDictionary) in

// use the data we just received

}PromiseKit has provided us with an extension on NSURLConnection that allows us to call promise(req:NSURLRequest) on it. After that we call then. The code that's inside of this closure gets called once the Promise is fulfilled. This happens whenever the request completed with success. If the request fails we can add a report ('catch' in swift 1.2) as well to make sure we catch that error:

var req = NSURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "http://example.com/api/feed/")!))

NSURLConnection.promise(req).then{(data: NSDictionary) in

// use the data we just received

}.report{ error in

// do something with the error

}And if there's code we want to execute regardless of error or success we can use ensure (defer in swift 1.2) like this:

var req = NSURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "http://example.com/api/feed/")!))

NSURLConnection.promise(req).then{ (data: NSDictionary) in

// use the data we just received

}.report{ error in

// do something with the error

}.ensure{

// perform action regardless of result

}If you understand this, you basically understand all you need to know to start using Promises in a very basic way. But let's get a little bit more advanced and start returning our own Promise objects.

Returning Promises

Imagine this, we're building an application that uses an API. We want to ask the API for a user's feed and we want to use PromiseKit for this. A nice implementation might be to have an API instance that has a method on it called fetchUserFeed. That method will return a Promise so we can easily use the result from the API in the class that actually wants the API to fetch data, a ViewModel for example. The fetchUserFeed function might look something like this:

func fetchUserFeed() -> Promise<Feed>

var req = NSURLRequest(URL: NSURL(string: "http://example.com/api/feed/")!))

return NSURLConnection.promise(req).then{(data: NSDictionary) -> Feed in

return Feed(dataDict: data)

}

}Note: Feed is a just a data object not included in the sample for brevity. It is used to illustrate how you would return something from a

Promise

The function above is very similar to what we had before except now it returns NSURLConnection.promise which is a Promise. The then of that Promise now returns a Feed and the fetchUserFeed function now returns Promise<Feed>. What this means is that fetchUserFeed now returns a Promise that will resolve with a Feed. So if we use this function it looks like this:

let api = DWApi()

api.fetchUserFeed().then{ feed in

// use the feed

}That's pretty clean, right? Now let's say that we not only want to fetch the Feed but also a user's Profile. And we want to wait until both of these requests are done (and successful). We can use the when function for that:

let api = DWApi()

when(api.fetchUserFeed(), api.fetchUserInfo()).then {feed, info in

// both requests succeeded, time to use the feed and info

}.report { error in

// one or both of the requests have failed

}Let's make this this a little bit more complicated shall we? Currently we're able to use an API to fetch stuff, and we're able to do multiple requests and wait until they're all complete. Now we're going to wrap that into a function we can call from somewhere else. The function will return a single object that uses both a Feed and UserInfo to create itself. Let's call it ProfileModel.

func fetchProfileModel() -> Promise<ProfileModel> {

let api = DWApi()

return when(api.fetchUserFeed(), api.fetchUserInfo()).then {(feed: Feed, info: UserInfo) -> ProfileModel in

return ProfileModel(feed: feed, info: info)

}

}And when we want to use this function we would write something like this:

let viewModel = DWViewModel()

viewModel.fetchProfileModel().then{ profileModel in

// use profile model

}.report { error in

// handle errors

}That's pretty cool isn't it? Pretty complicated logic wrapped in promises to make it simple and enjoyable again.

Wrapping it up

In this post we've touched up on the basics of PromiseKit, a library that makes asynchronous programming cleaner and easier. I've shown you how to use them in a very simple and basic setting and in a situation where you wait for multiple operations/promises and return a single promise with both results. Promises can help you to build a very clean API for your async operations and they help you to keep your code clean and readable. I highly suggest to try using promises in your own projects, they're really cool and easy to use. To find out more about PromiseKit you should check out their github.

If you have questions or feedback for me on this subject make sure to hit me up on Twitter or look for me in the ios-developers slack community.